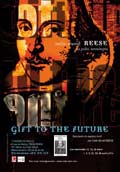

Gift to the Future

Gift to the Future

- De : Colin David Reese

- Avec : Colin David Reese

Spectacle en anglais.

- The memory of a friend and genius

1623. John Heminges returns to his house on the site of the Globe Theatre with a precious package: the first edition of William Shakespeare’s Comedies Histories and Tragedies.

As John starts to read through the plays, the memories come flooding back – of back stage intrigues, performances, successes and disasters and above all the importance of preserving the writings of a genius who, according to Ben Jonson, “was not of an age, but for all time”.

The very fact that Shakespeare is so well known and loved today is a testament to John’s dedication and firm belief in the work of his extraordinary friend. Without John Heminges, there would be no Shakespeare!

- Author’s note

As all biographies of William Shakespeare, this is essentially a fiction. The known facts about the man being that he was born, married, had children, bought property and died. The rest remains conjecture.

Gift to the Future brings to life what I consider to be a plausible vision of a man of the theatre as viewed by a life-time friend and colleague.

As a man of the theatre myself, the research that I have done over the years into the vast body of work written about the man, the theatre of the time, the social place of the players in Elizabethan/Jacobean life, has been naturally influenced by my own curiosity into what it must have been like to be a player on the boards of The Theatre, The Globe and subsequently The Blackfriars.

By illustrating the story line with readings from the plays, I have tried to show the eclectic nature of his creations. It is impossible to assess the character of an artist from his works. Imagine a psychologist trying to analyse Picasso from his paintings (or better still Jackson Pollock). Shakespeare created hundreds of very different personalities from his imagination, none of which gives us any real insight into the man himself. There are various contemporary references to Shakespeare which are for the most part highly complimentary (with one notable exception) and it seems that his reputation at the time was of a likeable person and talented ‘poet’.

Much of this research has been within the world of academic studies – written by academics, for academics. Many times I felt that the resulting works were missing the point. The plays were written to be “played”. Not as philosophy and certainly not as literature. A playwright, particularly a playwright working within an established company and creating parts for specific actors, has only one aim in mind – to create characters and a story that will live on stage and hold an audience. Furthermore the players of the time were working under a very specific set of conditions and so for the play to progress, much of what was written into the actors’ texts would be necessary instructions concerning what we in the modern theatre would consider to be “the direction”.

The theatre is ephemeral and all the indications point to the fact that Shakespeare considered his theatrical creations as such. It is reasonable to suppose that only Heminges and Ben Jonson recognised the eternal value of his works. Heminges being the financial and management controller of the company was uniquely placed to achieve the – what must have been massive – task of accumulating the disparate documents (cue scripts, plot sheets, prompt books, etc.) necessary to create the Folio.

That a man should consecrate so much time and energy to such a task at an advanced age (he was 67 at the time of the final printing) with little hope of financial reward for his efforts indicates a singular dedication to the memory of a friend and genius. A veritable “Gift to the Future” .

Colin David Reese

Vous avez vu ce spectacle ? Quel est votre avis ?

Informations pratiques - Nesle

Nesle

8, rue de Nesle 75006 Paris

- Métro : Odéon à 352 m, Pont Neuf à 395 m

- Bus : Pont Neuf - Quai des Grands Augustins à 103 m, Saint-Germain - Odéon à 300 m, Jacob à 357 m, Pont Neuf - Quai du Louvre à 398 m

Plan d’accès - Nesle

8, rue de Nesle 75006 Paris